On October 12, 2023 I have a new novella coming out in an anthology, My Fair Regency. It was fun to write, and something a bit different, and writing short always has its challenges. In this case, I wanted to write a story that takes place over eight years. The first challenge in that was keeping track of the timeline, and what was happening in each year. The next was keeping track of the settings over those years and what the characters and secondary characters might be doing. These were technical issues, but they do matter in that you don’t really want the reader noticing this stuff.

The other thing is that I like stories that focus mostly on the characters, and this means the conflicts are often subtle and not earth-shattering–it’s the small things that can matter a lot. I also wanted it to be a somewhat light, fluffy story–in other words, a lot of talking and ‘piffle’ and yet it has to have enough substance to stand up (even a meringue needs that). This meant it needed the theme to weave into the scenes, and the characters needed things that mattered to them–and those wants had to both evolve slightly, yet had to remain over eight years. That was the core challenge–dealing with the growth and evolution of the characters, yet having them hold to some core guiding lights.

Now, I like a technical challenge–but I try to keep it to only one per book. I found out early on when I started writing that if I bit off too many challenges (and I often did), the characters and story tended to bog down in those issues. I ended up forcing characters into a plot due to the technical stuff. This includes trying to deal with viewpoint, scene arcs, dialogue, conflicts, theme, paragraph and sentence construction, descriptions, and even word choices. Technique needs to serve the story–meaning it has to serve the characters. If it takes over, it can take the life right out of a story–the story steps into being an intellectual exercise instead of an emotional experience. But how does one get technique out of the way?

I think it’s possible to deal with technique in a couple of ways. The first is to become skilled with it–meaning write a lot. If you write enough, you stop having to worry about certain things. They become automatic skills. How you handle transitions, viewpoint, scene arcs, dialogue all becomes automatic functions that you can allow your writer’s instinct to deal with–you get that internal nudge when something isn’t quite right. The other way is to handle it with edits. Get the important stuff for the characters–their emotions, desires, personality–onto the page. Edits will allow you to check for rough bits, for things that don’t quite work. With edits comes the need for copy edits and proof readers to help out and point to mistakes and what’s missing–but don’t neglect a potential read from a beta reader who may find emotional moments that may be missing.

The other factor with a novella is that short is harder than long–there’s less room to go off on interesting tangents and amusing secondary characters. Every word has to count, and pacing is vital.

How did all this apply to my novella?

Well, you’ll notice there’s actually more than one technical challenge here, so I split them up. I left sorting out the timeline to the edits–I could more easily fix that during revisions. This allowed me to focus just on the characters while I was writing, and since I like to treat setting as a character that was included. I split up the other technical issues as well, but that is my habit–I have found I can write dialogue or I can write description, but I can’t do both at the same time. It is easier for me to write the dialogue, sharpen it, and then come back and put in any action or description I need to weave in subtext or contrast or use setting to amplify emotion or motifs. Or I can do the descriptions to set up a scene or create a mood, and then I’ll figure out the dialogue when the scene starts. Polish for all of this comes in another edit–and that’s where I have to use care to keep the mood the same and not edit out emotion.

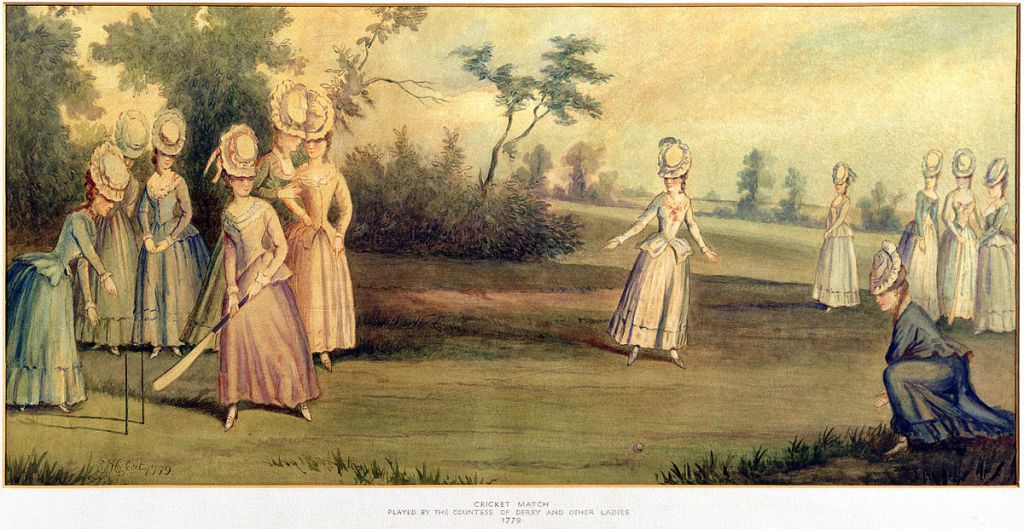

Finally, about the fun bits here–the anthology uses the Regency England setting of different holidays and fairs, so my holiday was Guy Fawkes Night, with its bonfires and crackers (fireworks to those of us in the US), and the other holidays used some of the lesser known events, such as Cheese Rolling, along with the better known May Day and Twelfth Night. For Guy Fawkes, I did do a bit of research–it’s still a rather rowdy event in England–but even more fun was weaving in events across the years from 1805 to 1813. With a bookish heroine, I was able to dive into scientific events, publications, and use apt quotes to mirror what was going on in her life. The hero is a more active person, out wanting to go places and do things, and join up with army during the Napoleonic Wars–a dangerous ambition. They were a nice pair, but when it comes to bringing them together, Guy Fawkes Night served nicely for that–it is a night when the unexpected can happen.

Hopefully, that is what this anthology is all about–the unexpected delights of new stories and new authors.

ABOUT THE ANTHOLOGY–MY FAIR REGENCY

Celebrate Regency romance all year long with this collection of short stories set during holidays and festivals throughout the four seasons! Fans of sweet romance will enjoy stories set from May Day all the way to Twelfth Night, featuring some of your favorite tropes—enemies-to-lovers, second-chance romance, forbidden love, friends-to-lovers, and more! The collection includes:

May Day Mayhem by Ann Chaney—Intrigue, death, and love come to Horsham-Upon-the-Thames as the small English village anticipates their May Day celebration. Home Office agents the Duke of Doncaster and governess Helen Stokes join forces to uncover a missing list of French agents before an enemy discovers it. Mired in May Day preparations while chasing hoodlums and gentry, Helen and Doncaster try to fight their mutual attraction in a romantic farce worthy of Covent Garden.

My Favorite Mistake by Courtney McCaskill—Sixteen years ago, lady’s maid Fanny Price was swept off her feet by a handsome horse trainer named Nick Cradduck. The very next day, he shattered her heart. But now, at the Cooper’s Hill Cheese Rolling and Wake, who should Fanny encounter but the man she crossed all of England to avoid… A second-chance love story featuring Fanny, the scene-stealing lady’s maid from How to Train Your Viscount!

His Damsel by Charlotte Russell—During her annual visit to Bartholomew Fair, Eliza Cranstoun is mistaken for a lady in distress when in fact she was attempting to avenge the honor of her cousin. Now, she insists Anthony Ripley, her savior, help her bring down a lordly scoundrel. Amidst the scheming however, the independent Eliza and the confirmed bachelor Anthony, discover that love finds even those who choose not to seek it.

When I Fall In Love by Cora Lee—The Harvest Festival is a chance for reunions and love, but perhaps not for childhood friends Sylvie Devereaux and Kit Mathison. When Kit returns to renovate the home he inherited, Sylvie’s financial burdens prompt Kit to propose a marriage of convenience. But Sylvie has always wanted to marry for love, and they don’t love each other…do they?

Remember by Shannon Donnelly—Over the years, Beatrice Foxton keeps meeting up with Andrew Cliffs on Guy Fawkes Night, but these two friends are separated by her family’s expectations for her to marry a well-born lord and his family’s background in trade. And, yet, they can’t stay away from each other…

The Aeronaut’s Heart by Regina Scott—Josephine Aventure was on her way to earning a place in England’s Aeronautical Corps until the dashing smuggler she’d once loved showed up. Etienne Delaguard risked much to help England win the war against France. Over a Twelfth Night masquerade, can a gentleman of the sea win the heart of a lady of the air